Expensive People

This was my writing teacher’s magic: He could burn you and make you glow.

Richard lived at the fountain. Or so it seemed. He was there, strumming the beater guitar he carried slung over one bony shoulder, when I left the dining hall after lunch and unlocked my bike. He was there in the late afternoon, his veiny legs sprouting from rumpled khaki shorts and a wide straw hat on his bald head, a greasy rucksack at his feet, in hiking boots and dingy socks, when I emerged from the music building, reeling from a brutal music history exam or a frustrating composing lesson. Nights when my creative writing class let out, I sometimes caught him packing up his guitar and ambling away from campus, always alone.

Richard was always there, around him a miasma of pot smoke and shapeshifting legend. Depending on whom you asked, he was: a hobo, a professor, a genius, a physicist, a lawyer, a beatnik, a billionaire, a felon. I spent a lot of time with Richard in those days, talking, though I managed to learn next to nothing about him. Once, he spotted the Joyce Carol Oates novel I was reading and asked if I knew what the title meant. I was well-practiced, by twenty, at coaxing approval out of old white men who were more well-read, or who claimed to be, than I was. I offered my best blue-book-ready answer.

“Nope,” Richard said. He winked and gave me a try-again smile. He could be cryptic and imperious, but Richard had patience for young people who found themselves fascinating for finding old people fascinating.

Around that time, I was taken on by, taken in by—and certainly taken with—my first writing teacher. I’d had other teachers, of course, even of writing, but never a writing teacher. A Writing Teacher is different from a teacher of writing the same way that Sunday School is not as simple as school on a Sunday.

I took to fiction workshops immediately, for the same reasons I once liked Sunday school. Every week promised stories, and even when we hit boring, pedantic stretches, I had a sense that this endeavor was making me better in some way or, at the very least, providing me with what I would need to get through a set of gates someday.

Sunday School, Writing Teacher: I don’t believe in either one anymore.

My first Writing Teacher was a sort-of-famous short-story writer. For years, at my instruction, when my mother found his pieces in the Washington Post magazine, she clipped them out and mailed them to me in the desert, and I saved them in a fawning file I still can’t bring myself to throw away. He was gregarious and handsome, with a big, circular face and a full head of white hair whipped into a precisely cut but youthfully disheveled style, like a movie star playing an athlete. He wore khaki pants and sneakers and crisply pressed Oxford cloth shirts. He seemed, always, delighted with himself and with writing and with all of us who circled around him, scooping up the quotable lines he fed us: “The writer is the person who wrote today!” We quoted him to one another at our parties and to ourselves as we tapped away at keyboards in the computer lab writing our stories.

I was lucky to get a spot in that first class with him. A rotator cuff tear sidelined me at home in Maryland the winter I was nineteen, and I went back to school two weeks into the spring semester of my sophomore year. An advisor in the English department, seeing that I was a music major but that I had taken creative writing in the fall with a different teacher, wondered aloud if she could get me, at this late date, into the sort-of-famous writer’s class. “I doubt if he’ll sign an override,” she said, “but we can try.”

She called his extension, and as she did, I recalled that a very kind high school teacher back home had told me about this writer when I’d told her where I was going to college. They’d taught together, decades before, at an East Coast boarding school. She’d even sent him a note of introduction when I’d first come to the school. On the phone, the advisor’s face went screwed up and squinty and it looked like she was getting ready to hang up, so I whispered, “Tell him I know N_____ S_______.” My advisor did, and immediately she was nodding rapidly, jotting a few things down, flashing her eyes at me, smiling, giving a thumbs-up. “Well,” she said as she put the phone back in its cradle.

“What did he say?”

“He said the stars have crossed in your favor, and you can come to class this week.” She handed me an override form for the Writing Teacher to sign.

That first night, the class was workshopping a science-fiction story. My new Writing Teacher looked down at his copy of the boy’s story. “It says here ‘Chapter 1.’ Does that mean there’s more of this?”

The boy grinned and drawled “yes,” his head dipping in an oversized nod.

My new teacher, it seemed, was discovering an up-and-comer right in front of me. I pictured him phoning his agent in New York right after class. A rapture is thrilling to watch, even if you’re left behind.

“No,” the Writing Teacher said, beaming. “No. Stop. Chapter 1 is all you get. You’ve used up your lifetime allowance of jet packs.” This Writing Teacher was the sort—and now I have had several others—who made declarations about what you could never put in a story: I wasn’t inclined to put jet packs in my story like my new classmate, but it seemed probable that, given my childhood in Maryland, at some point I would violate the prohibition against slamming screen doors. The boy hadn’t been discovered by the sort-of famous writer, in fact the opposite, but he grinned and guffawed like he had been, the whole time we workshopped his story. This was one form of my Writing Teacher’s magic: He could burn you and make you glow.

After class, I went to the writer to have him sign the override form and to find out what assignments I had missed. As he scribbled his name on the form, he told me my story was due at next class and I also needed to do his elaborate writing exercise and read all the previous weeks’ workshop stories and write critiques as well as a letter to him about which of those stories was the best and why. All of it was due at our next class. “No problem,” I said, because it was clear this was a test to find out if I’d earned my override, mutual friend notwithstanding.

“Oh, also,” I said. “I made these pants.”

“What?”

“You said a little bit ago that no one sews their own clothes anymore. I made these pants.”

He had no recollection of the declarations he’d tossed off as truth. Things I’d written into my notebooks like formulas. “Well,” he said, smiling, stuffing next week’s stories and books into his beat-up leather shoulder bag. “You’re a throwback.”

For the next twenty years—from this night a few weeks before I turned twenty until the summer that I turned forty—I loved him, and I idolized and emulated him.

I use the past tense, but my Writing Teacher isn’t dead.

My defection from musician to writer was pre-ordained. I grew up in a house of books: My mother had shelves of novels and poetry, along with the nursing and medical books that filled low shelves behind her desk in a corner of the family room. My dad had books about physics and architecture and guns and history in his tiny den, where after work and on Saturdays since around the time I was born, he’d been working on his own book about the Victorian railroad stations of E. Francis Baldwin.

On the bricks beside our fireplace, next to the aquarium where we kept the hermit crabs we’d gotten at the beach in Virginia until they crawled under the couch and died, we had a wicker basket for library books. Library books needed special shelter in our home to prevent them from being subsumed by the churning tides of books we owned: Where the Wild Things Are, and Judith Viorst (signed) and every Shel Silverstein in hardcover, with its irresistible philosophy-disguised-as-play:

How many slices in a bread?

Depends how thin you cut it.Among our permanent collection of books was a little volume of bedtime rhymes we checked out from the library over and over, a slim hardcover inside a paper dust jacket, with illustrations that filled every page—dark, fully saturated drawings in colored pencil or watercolor that bled to the edge of the page. This book lived on one of the shelves in our family room, and even when I’d officially outgrown it, I loved to go to it, bedtime or not, and read my favorite: “When Daddy Fell into the Pond,” by Alfred Noyes:

Everyone grumbled. The sky was grey.

We had nothing to do and nothing to say.

We were nearing the end of a dismal day,

And there seemed to be nothing beyond,

THEN

Daddy fell into the pond!Preposterous! Hilarious! What business did a daddy have at a pond? I’d been with my dad to lakes. We’d visited many of the 10,000 lakes of my parents’ home state; we’d camped at Deep Creek Lake. I’ve been told the family went ice-skating at Lake Needwood, just miles from our home in Maryland, when I was so small I wore double-bladed skates. Lakes, yes. But ponds. I couldn’t fathom a circumstance that would put a daddy at the edge of the mucky, radioactive-green oval behind my elementary school, or Hansen’s Pond, where my sixth-grade teacher took us on a miserable field trip, the purpose of which, as far as I could tell was to feed us to the hungry insects of Maryland. Ponds I had access to, yes, but not a daddy—I don’t think I called him that long after about the age I learned to read—and if I was near a pond, say for a Girl Scout picnic or a field trip, my dad wasn’t there. He was busy with his top-secret work at a famous building in suburban Virginia or he was in his den typing his book or he was in Baltimore alone, taking pictures of Victorian railroad stations. He was dressed and dry and his glasses were on his face where they belonged. This dad of mine wasn’t in any danger of falling into a pond.

And even if he had been the kind of dad to volunteer for chaperone duty, my dad, a physicist, would never have been bested by a sloppy slope. He’d have sized it up: he would have inched down sideways; he would have dug in his heels; he would have made tiny, muddy switchbacks. He would have known without calculating—and then calculated, for sport—the precise grade of this shore’s slope and he would have known to position his center of gravity just so over his long, pale legs to avoid falling into the pond and if anyone was blithely traipsing—a word he would have used, for sure, or careening or gallivanting willy-nilly—toward this pond, he would have told them how to do it right, whether they asked or not.

When I started writing this, my dad wasn’t dead.

The last coherent conversation I had with my dad, I called him from a weeklong writing conference in Florida. It was his first whole day in his new home, an assisted living facility in Maryland called Sunrise, which occupies the place where the AM radio station WINX used to be, where one or the other of my parents had to drive a pre-teen me to pick up the Lionel Richie LP or Spuds Mackenzie T-shirt I’d won from a call-in contest; a half mile from where a musty, crowded wonderland called Book Alcove used to be, where I once bought a book of poems because it had a diary entry dated 1898 stuck in its pages; across the street from my high school where that kind English teacher told me I just had to meet her friend, the sort-of-famous writer she knew from her boarding-school days. Some rooms in the Sunrise tower peer down over the Catholic cemetery where F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, are buried—although local lore has it that their bodies have by now slid down under street. Nevertheless, the grave markers are there—“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past”—in the shadow of the place where my dad lived then, with cancerous prostate cells congregating in various places in his brain, making it impossible for him to keep his balance, see clearly, walk assuredly, and, worst of all, think.

“How are you doing, Dad?”

“I’m useless. I can’t think.”

“You’ll never be useless to me.”

“Maybe as an artifact. Pay no attention to the cabbage plant in the corner.”

Actually, I’m not sure if that’s what he said. It was something like that. I should have written it down. I should have written down everything he said.

Four times in that call, my dad told me the same story about how he’d met someone in Sunrise from a town in Maryland about which he knew a million interesting things about railroads and trains and Korean war vets but he couldn’t summon the things he knew. He knew he knew them, but he couldn’t pull them up. “I wished I’d had a copy of my book”—that book about Baldwin he’d been researching and typing and photographing all those years had become a real, bound thing—“so I could show him what I wanted to tell him. I can’t think.”

“Do you have your book there?”

“No, it’s packed up. I can’t think.” My dad’s townhouse—a few miles away, still his, still full of National Geographic magazines and log books for every tank of gas he’d bought since 1956, and the wind tunnel he’d built in college, and his physics dissertation, and the books from our home that were designated his in the divorce, almost exclusively nonfiction—would need to be dealt with at some point.

“I’m sure someone can bring it to you.”

“I can’t think. How are you?”

“I’m in Florida.”

“I know. I did remember that. How is it?”

The writing conference was held at a strange little college in Florida. The campus was dark and well-treed, with squat, white-brick buildings in need of a new coat of paint. Walking paths were wide and sinuous and impractical, and they’d end without warning, depositing me at the lip of a bog. It was January but there weren’t any college kids around, just abandoned bicycles lashed to rusting racks. The whole place felt to me like a horror-movie Chutes and Ladders, with the exception of the gleaming, modern library, which sat glowing over the whole grim campus like a dying star. After each day’s three-hour workshop with a Very Famous Novelist, I skipped most of the craft talks and went to the library to read Paul Harding’s Tinkers, which I’d grabbed from my shelf for the trip because it was small and lightweight, not realizing I’d brought along a manual for surviving not my dad’s death but his dying.

“It’s okay. I’m not very good at making friends,” I said. “But I walked eight miles around downtown on Wednesday.”

“Well, yeah, that’s what you did when you went to Kentucky, too.” He didn’t mention—did he remember?—that the day I explored Lexington by myself a few years before, I’d passed out in a café and ended up in an ambulance and then the hospital where they gave me some electrolytes and sent me walking back to my hotel.

“I really like walking alone around a city I don’t know,” I said.

“Are you learning anything?”

“My workshop is good. I like my teacher.” The little notebook in my bag was full of things the Very Famous Novelist said to our class each morning, mottos he’d collected from other very famous writers, like, “The writer must clear her throat before she sings.”

“Well, be careful,” he said, and I know he meant be careful walking alone around an unfamiliar city, not be careful writing down in a precious notebook everything your Writing Teacher says, but I was old enough then that I knew to take it both ways.

“I love you,” I said before we hung up, and he said it back, a thing he did easily then, though for many years he was stingy with it and occasionally he infuriated me by saying thank you when I said it to him.

At my second class with my Writing Teacher all those years ago, I turned in all the things he had asked of me and, the week after that, we workshopped my story, a double-spaced, 12-point, Times-New-Roman manuscript entirely free of jet packs and slamming screen doors.

My story was a cold and dreadful thing called “Ice,” in which a free-spirited young woman of indeterminate age goes ice-skating with her father, a man who has apparently ruined her life by always explaining, in scientific terms, the things she thinks are magic, such as the ability to swing a bucket of water around above your head without spilling it. The girl has long black hair, so the reader can trust that this is fiction; the girl is not me. The girl falls while skating and, despite being a young adult, she cries, mostly because she feels that her father does not understand her and never will. The father in the story asks the girl why she is crying, and the girl cannot say, “I feel far away from and misunderstood by you,” so instead she claims that her tears are freezing to her face. “It hurts,” she says. The dad scoffs and explains that her tears can’t be freezing to her face, on account of the saline content of tears and the moderate outside temperature, not to mention the temperature of the body from which the tears flow. The girl—a pallid anygirl, a non-character, her fictional black hair the only real thing about her—limps off the ice feeling even further from her remote and scientific father who, in my not-yet-twenty-year-old authorial hands, is a cartoon: at best, a two-dimensional autist, at worst a cruel Vulcan in a black turtleneck.

At our third class together, my Writing Teacher said, “Okay, Andrea’s up for workshop. Andrea has written a very clever story.”

I straightened up in my chair, felt the eyes of my classmates on me. They would witness my rapture. But then the Writing Teacher turned his big, open face at me and said, “Don’t ever do it again.”

At the break in the class, my Writing Teacher asked me to accompany him to the coffee kiosk, in the middle of campus. As we walked, he asked me about our mutual friend, my high school teacher; he praised the “clever” story he’d just finished disassembling; he asked me about my major (music?) and my sewing (did you really make those pants?). At the end of class, he handed back the other work I’d turned in, and at the bottom of my writing exercise, he’d written “superlative work.” A decade later—after he’d let me take his graduate workshops as an undergrad; after he’d written me letters of recommendation for MFA programs, which he told me he’d sent “off into the world where I would be soon, on my sterling trajectory”; after he’d sat on my thesis committee because I’d decided to stay put for my MFA and study with him—he published that little exercise in a literary journal he was guest-editing.

As for the terrible ice-skating story, he’d written “wonderful bath of images”—ice bath, maybe—and “girl: her life now: into what life has this day come?” I know exactly what he wrote on this manuscript, because I kept these artifacts even after I’d pitched my classmates’ critiques. I kept my Writing Teacher’s comments on every story I wrote for all the years I studied with him, and I have them all, still, tucked neatly into hanging files in my desk drawer.

For many years, I thought I’d have—I thought I had—one of those lifelong literary relationships with him, the kind inventoried in A Manner of Being: Writers on their Mentors. I planned to remain dear to him and he to me; we’d be braided into one another’s dilating-contracting families; over decades our exchanges would become collegial and then the shoptalk of peers; the first-draft reads and margin comments and book-flap inscriptions and acknowledgments would flow both ways. I wanted from my Writing Teacher what George Saunders describes having in Tobias Wolff: an honest and generous and gentle and steadfast and indisputably good person to model oneself after and to also occasionally get drunk and sing with. Is that a greedy, unreasonable want? Perhaps, but my own Writing Teacher had had it from his teacher, and I wanted it from him. Truly, I wanted that as much as I wanted any other part of a writer’s life.

Until I was twenty-six and finished with my MFA, I saw him almost every day: in his classes, at his readings, TAing for him, watching him, listening to him, reading him, writing down almost everything he said. When I became a teacher myself, I parroted his lines: “The writer is the person who wrote today!” I told my students, and “Put feathers on all your characters!” and “Into what life has this story come?” All those years, whenever my Writing Teacher published a book, I bought it in hardcover and asked him to sign it. He always turned to the title page, wrote a pithy personal message I’d wait to read until I was in the elevator, like a Valentine, and then he drew a slash through his own name and signed above it. I decided that if I ever published a book (Oh, having a book to sign—just one book!—would make me happy forever and I’d never want anything more), I would do it just that way, too.

And I do. Even knowing what I now know about him. When I do signings, I sign just the way he did. I copy him, even though I am aware as I flip to that page, as I scrape a diagonal black slash through my name on the page, I know it is a seamy affectation. Even though, at the writing workshop in Florida, the Very Famous Novelist told us in our morning workshop that “sincerity is never having an idea of oneself.” Ever dutiful, I wrote that in my notebook.

But how to square that definition of sincerity with love for the teacher who gave you an idea of yourself in the first place? The person who literally stamped my ticket and let me in? I had found in my Writing Teacher what Sheila Heti describes finding in Susan Roxborough: “one figure of understanding in order to not feel they are a random, spinning particle in the universe, without destiny or care.” I swooned, every time, at his last-day-of-the-semester lecture: what do real writers do on the last day of school? They stay, stay in the quiet schoolhouse after the bell, they stay and they write, while the others—lesser people—dash off at the final bell, tossing off papers and books toward what they misconstrue as freedom. My Writing Teacher invoked the secret knowledge that finding a quiet space to make up stories was the most wonderful thing, affirming our (that is, my) place at the writer’s table. His lecture was to me as holy as prayer, as comforting as a Robert Louis Stevenson bedtime rhyme:

What are you able to build with your blocks?

Castles and palaces, temples and docks.

Rain may keep raining, and others go roam,

But I can be happy and building at home.

I was supplementing my Writing Teacher’s coursework with impromptu Socratic seminars with Richard at the fountain in the middle of campus. Some of the whispered lore about Richard turned out to be true—though he never disclosed any of this to me himself: he was educated, with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering. He was well-traveled, having lived abroad in Italy and Scotland. He’d been a professor, he was a writer plugging away at an enormous manuscript, and he was at least semi-indigent, making his home during the years I knew him in a shack or a van. I learned all this only after Richard was dead.

And by the time he was dead, buried by a chain gang in an unremarkable grave in a sunbaked potter’s field, I had fallen out of his orbit. Twice-graduated, moved on. He was a quirk of my adolescence, a story swapped with my husband when we compared notes about our overlapping time on campus, long before we’d met. “Did you ever see a skinny old guy at the fountain? His name was Richard. I used to, like, hang out with that guy a lot.” Subtext: I am so original, so unusual. But I returned frequently to the puzzle of that novel and its cryptic title. I wasn’t bothered enough to re-read the book—I’ve read my last Joyce Carol Oates, that’s for sure—but from time to time, it tugged on me: What did the title “mean”? And how could Richard be so sure he knew, and that I was wrong?

“You don’t know yet what your treatment options are,” I said to my dad on the phone from Florida, that first month of the last year of his life. “Maybe they can do something to make you feel better. Like before.”

“And what? This happens every January,” he said. The first brain tumor had hinted at its presence with wobbliness he didn’t report to anyone until he plain fell over on New Year’s Eve, decided not to go to work, and went instead to the hospital where, days after surgery, he was grumbling about not being at work. The next year, nearly to the day, he turned up with another tumor and underwent another surgery, more radiation, chemo. Now it was January again, tumor season again, and it wasn’t clear yet what the treatment approach would be for an eighty-year-old man with cells hell-bent on clustering in his formidable brain.

“I can’t do anything. Can’t move around, can’t think.”

I haven’t witnessed much of the unsteadiness, the vertigo, the rapid cognitive decline, but of course I believe my mother, my sister, my brothers, who all live so much closer, who see him and help him more than I do. He has been slowing down, stumbling, tripping, they tell me. It’s not good. I haven’t seen it. I—Is it really possible that I have never seen my father fall down?

The closest thing I can think of happened on one of our annual camping trips to Chincoteague, Virginia. We went almost every summer, “as soon as you were out of diapers,” my mom tells me. In Chincoteague, my dad built fantastical sand sculptures on the beach and the sun made him pliable enough to consent to Dairy Queen or saltwater taffy or those doomed hermit crabs. We slept, all six of us, in a humid blue tent, the floor a mosaic of sleeping bags and paperbacks. Once, we rented bicycles and my dad perched backwards on the seat and pedaled over a bridge while we cheered until he almost collided with a man, someone else’s dad, riding the right way on the bridge and the man yelled at my dad, and I wanted to push that awful man, someone else’s dad, into the Atlantic for ruining my dad’s rare moment of generous, impractical hot-dogging.

That first thing I wrote for my Writing Teacher was not a fiction, but a lie: My scientist father didn’t diminish the magic of my world at all; he doubled it. He gave me the gift not only of a full bucket invulnerable to spillage but also of a melismatic word—centripetal force—to describe it. He agreed with me, nose wrinkling, that the garage smelled kind of nice after he’d mowed the lawn, and he bequeathed to me a name—oxygenated hydrocarbons—for the sweet perfume of clippings.

Once, when I was in college, before I’d given up on being a musician, before I met the Writing Teacher, I came down with a cold. I lay around my dorm room all day sucking on zinc tablets and, when I felt better, I walked down the street to the deli, where I ordered fresh-squeezed lemonade. After only a few sips, my mouth had gone slick and foamy. I rushed to the pay phone and called my dad. “What’s happening to my mouth?” I asked.

“What have you eaten today?”

“Nothing! Just zinc tablets.” I panicked. I thought of the description of rabies in Symptoms, of Cujo.

“Just zinc?”

“And lemonade.”

My dad was quiet for a minute; I could picture him thinking. Then he laughed. “Well, honeybunch, you’ve gone and made soap in your mouth.”

Why didn’t I put this dad—funny, devoted, dear, and so very good—in any of the stories I piled on my Writing Teacher’s desk, year after year?

At the writers’ conference in Florida, on the very first night, as the group moved from the opening reading to the tavern for a welcome reception, I approached the Very Famous Novelist I knew would be workshopping my novel. “I’m in your class this week,” I said, and I fell into step with him.

In the quarter mile we walked together on a poorly lit, serpentine path, he asked friendly questions to which I provided breathless, excessive answers. When he asked a benign question about my writing, I managed to tell him about the memoir I’d published two years before. When he asked where I’d gone to school, I told him; when he asked who I’d studied with, I told him the name of my Writing Teacher in a strange voice. Ever since I learned the truth about my Writing Teacher, I’d said his name out loud only to my husband, my parents, my sister, the few former classmates I was still in touch with. With these women I had halting conversations when we crossed paths at conferences: “Was I the last to know this?” “No, I think I was.”

“Ah!” the Very Famous Novelist said when I choked out my Writing Teacher’s name. “He’s a friend. I’ll be quoting him this week.”

For three hours every morning of that week except for Wednesday—a day off for recharging, according to the conference agenda—my class of twelve wannabe novelists huddled in a crowded room for three hours as the Very Famous Novelist regaled us with stories and led critiques of our writing. The Very Famous Novelist was also the Very Friendly Novelist. All week long, in addition to dispensing quotable bits of writing inspiration for our notebooks, he brought out bags of nuts and chocolate two hours into each morning’s workshop and passed them around the table to share. There were no jet packs in my classmates’ novel excerpts, but the Very Famous Novelist didn’t seem the type to prohibit them or even slamming doors. (At one point, though, when I said that a line in a classmate’s story was funny, the Very Famous Novelist told me, unequivocally, that it was not.) When one of my classmates presented for our workshop a brutal rape scene, and told us it had happened to her, the Very Famous Novelist took off his glasses and leaned forward in his fleece vest and said, “I am so sorry that happened to you. I am so sorry.”

The Very Famous Novelist said to the woman who’d been raped and written about it, “These men who do this, these things—I just want to kill them. All of them.”

On the whiteboard behind him were the writing craft quotes he planned to feature in the day’s lesson. The last, a catchy thing about details I’d heard a hundred times before, was attributed to my first writing teacher. I looked at the letters that spelled his name, a name once as familiar as family.

Memory is a greased pig. When did I learn that Richard from the fountain shared a name, first and last, with the narrator of that Joyce Carol Oates book? Did I know it twenty-five years ago, when he quizzed me about the title’s meaning? Or did I learn it later, digging up the 1968 New York Times review of the novel to see if I could resolve Richard’s riddle once and for all, and then wandering into a Google search for Richard himself, which turned up a biography of sorts, written after his death, by a professor emeritus who knew him as well as anyone? Richard Everett was indeed a felon, convicted of assault and endangerment for abusing his daughter so severely that she spent the rest of her life in managed care, where I suppose she sat while her father, having discovered the Chinese divination manual The Book of Changes in prison, held court at the campus fountain. The online memorial parsed Richard’s philosophies: “He did not feel or express appreciation for those who assisted him,” the professor explained. “He expected helpers or hosts to feel appreciative for assisting this wandering ascetic to serve whatever path the I Ching discerned.” I’ve never been able to recall how I first met Richard, how I ended up talking shitty JCO novels with the mysterious fountain man. “Richard would never initiate a discussion with a student,” the admiring professor wrote. “He would only talk to those who spoke to him first. …[h]e never used the personal pronouns I or me.” If such became needed, he would refer to himself as ‘this guy.’ He was firm about this.” Hard to picture, then, Richard Everett revealing his full name to me.

The last time I saw my Writing Teacher was at yet another writing conference. At this other, west-coast conference, the line between faculty and rank-and-file attendee was blurrier than at the stodgier Florida conference, and it was not unusual for writers who’d paid to be there to find themselves at boozy late-night singalongs in chichi ski cabins with writers or agents or hotshot editors who were being paid to be there, and if you could play the banjo or sing the harmony parts, no one much cared which group you belonged to.

Shortly after I’d graduated with my MFA, with his name on my thesis, my Writing Teacher left the university where I’d met him under a cloud that I understood then to be merely that he’d been a bad husband. It wasn’t my business.

In the sixteen years since, I’d seen him only a handful of times: When I had knee-replacement surgery, he came to my house to visit me. A couple years later, he came back to town from California, where he lived now, and did a reading, after which he invited me to join him and his ex-wife for dinner at his old house, the same house my parents and my sister and my not-yet-husband and I had gone for a cookout after my thesis defense. On another occasion, my husband and I met him on our way to Catalina Island. We drove to a Starbucks he’d chosen and, promptly when an hour was up, my Writing Teacher stood to leave and told us exactly where my husband and I should go to lunch. We took his directions without question and drove to the adorably down-market hamburger stand he’d sent us to, without discussing it, without considering whether we were in the mood for burgers. I’d seen my Writing Teacher over the years, and I’d e-mailed him as I struggled with querying and agents and rejections and job-searching.

But at this conference, I would get a chance to be his student again—to go to his craft talk with my little notebook and write down the things he said. The summer was a hazy stretch defined in retrospect by its location between the Pulse nightclub shooting in June and the coming fall’s “grab ’em by the pussy.” For me, that summer was a long, surreal midpoint between selling my book and seeing it on the shelf. I bounced between relief and disbelief. Publishing a book turned out to be not at all the big moment of arrival I’d once dreamed of, but it brought with it all kinds of delicious smaller moments I hadn’t even known to dream of: like getting to tell my Writing Teacher, in person, that a thing I’d worked on for ten years was finally going to be out in the world.

On the last night of the California conference, out on a big patio under an alpine sky, we all ate a big picnic dinner and drank beer and wine while we waited for the sun to set and the conference talent show—exactly like every last-night-of-camp talent show, but with famous people—to begin. I sat at a table with my Writing Teacher, but no one else filled the other seats. Every so often, he’d offer to get us another round of drinks from the bar, and after about three glasses of wine, I told him in stark, unveiled, unclever terms how grateful I was that he’d been my teacher. That he’d taken a chance on me, that he’d poured his time into me, that he’d helped me. I’d never spoken to him that way, but middle age and wine and the deep satisfaction of selling a book I’d been working on for ten years had made me direct and open-hearted in a way I hadn’t been when I knew him before. I think I told him I loved him.

I don’t remember what he said to that, but I do know that on this night, before the talent show began, as we sat in the chilly, mountain near-dark, he didn’t say anything golden or quotable. He offered me a jacket. He seemed serious and old and tired and, for maybe the first time, totally sincere. For the first time since I’d met him almost twenty years before, he didn’t script the interaction and dash off when it was over. I thought, I finally met the real man.

How much love inside a friend?

Depends how much you give ’em.My last good day with my dad was on a perfect fall day before his final brain tumor and death the next year. I was in town for a book event to which both of my parents accompanied me. We stopped at Starbucks before and TJ Maxx after; my dad had never been and was dazzled by the bargains. He bought a laptop bag, a frying pan, and pants. I wore a pretty dress and patent-leather shoes, rode in the backseat of the car like a child, basking in the crisp October sun and the undiluted love of both of my parents.

How much good inside a day?

Depends how good you live ’em.At the reading, I signed books like my beloved Writing Teacher had done, a black mark through my name. Even though it was year two of #MeToo. By then, I’d read a brave and gutting essay by my classmate about our beloved Writing Teacher. I understood, belatedly, that he’d been more—or less, I suppose, much less—than just a philandering husband. I’d read the full report prepared for the board of trustees at the East Coast boarding school where he’d taught all those years ago with my high school teacher, identifying him by name as a sexual abuser of a girl—Student 17—in his class. And I’d read the essays in response to my classmate’s essay, in response to those older revelations, which identified my teacher not as an anomaly but as a member of a class, which located him in a constellation of predatory mentors.

I lingered, waiting for the Very Famous Novelist after workshop. I waited as he put his almonds and his books back in his bag. My Writing Teacher’s name, his quote, remained on the board.

“Hey,” I began, haltingly, “I know you said you really hate men who do bad things to women, and, well, this isn’t my story to tell, but I thought you should know that he.” I pointed at the board. “He’s done some of those things. To women. You don’t know who’s going to be sitting in your class, right, and how that would land on them? I just thought you’d want to know.”

By then we were walking together out of the classroom. “Thanks for telling me,” the Very Famous Novelist said. “But what are we supposed to do? Throw out good work? Are we supposed to stop teaching Ezra Pound?”

Now I have done with it, down let it go!

All in a moment the town is laid low.

Block upon block lying scattered and free,

What is there left of my town by the sea?Almost to a man, my mentors have profoundly disappointed me. In big ways, like my first Writing Teacher, and in small ways like my second. Mentor 2 was himself a former student of my Writing Teacher. He enlisted me to babysit his children, asked me to read and comment on his novel-in-progress, declared me “family.” I came to know and love his wife and his three beautiful children. But he did not thank me in the novel’s acknowledgments, and when my own book came out, he did not make it to my book launch. His marriage was buckling then, and my friendship had been transferred into his wife’s column. The last time I saw him, he narrowed his eyes at me, tightened his jaw, and kept walking.

Would I have now the lasting literary relationship I so wanted if I’d hitched my wagon to a Writing Teacher who was a woman? In her contribution to A Manner of Being, Paisley Rekdal (her mentor: no one) writes:

I’m part of that odd generation of women taught by an increasingly

mixed though still male-dominated teaching profession, one for whom

the most visible literary giants were primarily male.I came up a few years behind Rekdal, but there was just one woman on the fiction faculty when I did my MFA. Though I liked her, and I’m still grateful she made me read Colette, I didn’t find in her what every aspect of my education had primed me to see in my Writing Teacher, what Rekdal so aptly describes as “a person who has a stake of his own in your developing career and who hovers between father figure, teacher, and aide-de-camp.”

Something tells me that if Richard Everett had been a bag lady, an old, indigent woman parked at the fountain in grimy secondhand clothes, no one would have hung on her mutterings, speculated that she was a genius or a physicist or a billionaire, puzzled over her koans, indulged her idiosyncrasy, pardoned her cruelty.

Thinking of my Writing Teacher now disturbs me on several layers. First, I am angry that he hurt women: women I know, and women I don’t. And I am ashamed that I traded on cartoonish imagery of my dad—who was good, and who is gone—to earn my Writing Teacher’s approval. I am disturbed that I’ve so modeled myself after him as a teacher and as a writer. It’s not just one-liners to my students, gestures, and affectations like the book signing. It’s the voice in my head as I write, the one that says no, that’s too much, don’t be sentimental, don’t be cute. It’s the sneering prohibition against genre fiction, delivered not only as matters of aesthetics but of taste, of character, with the weight of moral proclamation. It’s don’t be clever, when my cleverness is among the things my dad liked best about me, that I like best about myself. This is not a call for cancellation. If there’s any space where I can make banishments and declare people unwelcome it’s here, in my head, in my writing, in my very own city of blocks.

How many slams in an old screen door?

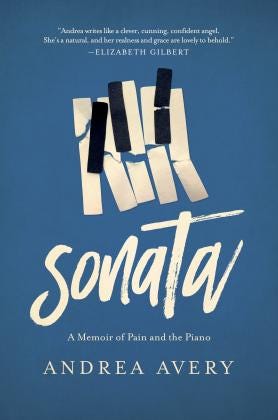

Depends how loud you shut it.Andrea Avery is the author of Sonata: A Memoir of Pain and the Piano (Pegasus Books). Her work has appeared in Ploughshares, Barrelhouse, CRAFT Literary, The Oxford American, and Real Simple, among other places. Her novella, Visiting Composer, was named the winner of Miami University Press’s 2024 novella contest and will be published in 2025. She lives in Phoenix, Arizona. She is working on a novel.