Ulrich, who can charm mustard off a bockwurst, finagles me a sublet flat in Charlottenburg from a proper and exacting woman. The landlady is named Frau Weingartner—“winemaker”—though I never feel the bounty of alcohol in her presence. As her son, Ulrich’s gymnasium acquaintance, is himself off to study physics in Indiana, it makes cosmic sense for an American to stay in his apartment. Ideally set up, spic and span, it sports a long and narrow kitchen and substantial pantry, as well as a compact bathroom, a storage room, and an ample living area for sleeping, studying, and entertaining. Facing south, overlooking a quiet courtyard, the apartment embraces the sun—though only a mere trickle of rays emerges in a winter seeming to last ages in late ’88 and early ’89. The building itself sits directly across garden allotments by the station Jungfernheide, whence I can travel to anywhere in the western part of the city by the U- or S-Bahn, Berlin’s main subway lines.

Heating is provided by a beautifully crafted ceramic Kachelofen or tile stove, supplied with coal kept in the cellar. Since the flat sits on the second floor (American third floor), this means multiple flights carrying metal pails whose handles dig into my palms, weighed down by coal briquettes from the cellar on the way up and ashes on the way down. After a time, I exploit two American chums, who carry enough fuel for weeks in exchange for dinner. When a ton of coal arrives, I count the number of bundles the men carry on their backs to the cellar. A friend confides they hate it when she does the same, but one shouldn’t be cheated.

The Berlin coal aroma becomes my Proustian madeleine.

Ulrich negotiates my rent. The first of every month, I leave an envelope filled with cash on a plate set upon the doily-festooned wooden kitchen table. If I’m not at home, Frau Weingartner lets herself in with a key she has retained to make sure—I suspect—that this untamed American woman is not throwing wild parties. Little does she know, I am almost as proper and exacting as she, though in an entirely different register.

Frau Weingartner would have frowned upon my more nefarious activities in East Germany, but as far as West Berlin was concerned, I was a model citizen. So much so that I became registered as a West Berlin resident, allowing me various perks while traveling across the wall into the German Democratic Republic. These included the ability to stay in the Hauptstadt der DDR—Berlin (East)—for up to twenty-four hours. This permission, in turn, required the address of a contact. But my story here does not cross that particular border.

Initially, I had no proof that Frau Weingartner poked around the flat when I wasn’t there. One day, a neatly handwritten note is left on the china plate requesting that I close the curtains of the living space while absent so the carpet won’t fade—though how anything could fade in the thin, weak light of chilly Berlin (West), I can barely imagine. Another time, Frau Weingartner reminds me to leave the garbage outside the door in a plastic bag for the concierge to pick up twice a week. Her hovering and spectral presence means I have to endure oversight.

Spies exist in both East and West Berlin.

I have only one issue—a teensy-weensy problem—with the flat. I’m the first to admit it is due to squeamishness. The toilet has begun to—there’s no other way to put it—clog. Due to leave for a ten-day teaching trip in East Germany, I have no time to tend to this slight inconvenience. Every time I flush after—shall we call it Number Two?—most of my waste and paper stay in the bowl. I then fetch one of the plastic shopping bags Frau Weingartner insists on being left out for the concierge. I manually fill it with my toilet paper and even—dare we say it?—filth. I hang it on a hook embedded in the door of the pantry off the kitchen, a door I typically keep closed.

Why is the toilet not flushing properly? I can’t imagine what the problem is. Why am I forced to live as though I were in the woods? Even that would have been better. I have peed and pooped many a time on Girl Scout trips in the open air. This is somehow unnatural. Yet I have no choice. My visa is set, my students await, and I am in no way going to mess with the government of the German Democratic Republic to delay my trip for a mere ill-placed turd or two.

I merrily head off to teach in Rostock. Upon my return, I enter the flat, exhale, and relax.

Until Ulrich calls. He is privy (no pun intended) to her schedule. “Frau Weingartner is furious!”

“What?” Oh dear, she has discovered my illicit plastic bag of effluence.

“She went into the flat” (which maybe she shouldn’t have been going into anyway), “and the toilet exploded.”

“Exploded?”

“She flushed and it exploded!”

“How could it have exploded?”

“The lower flush was fine, but the harder flush wasn’t.”

“Lower flush? Harder?”

“You know. How the toilet has two flush settings.”

“What?”

Silence at the other end of the line. Then, “You do know you press a light flush for pee-pee and a longer flush for Scheiße?”

Silence again, though now from my end of the line. Then I say, “No. I think I was just doing the light flush all along.”

Well, that explains that.

Ulrich thinks me a “dear little idiot,” for that is just what he calls me. “I will let Frau Weingartner know. It would help if you apologized.”

“Of course! Of course!”

Light flush? Hard flush? This was something new to a girl used to pulling chains in England. A vague memory of Erica Jong ascribing German toilet construction to the same mentality that concocted the Final Solution flashes in my mind. I might add at this point that thirty years later, upon revisiting the building of my one-time flat, I tripped outside the threshold. There, embedded in the sidewalk, exactly where I had crossed thousands of times, were Stolpersteine—golden markers commemorating Jews who had lived there only to have been murdered in Nazi extermination camps.

After the phone call, I check the pantry. Opening the door, I discover the plastic bag sloshing around, pristine—so to speak—and undiscovered. A sigh of relief.

The next day, after I have unpacked and slept, I write an unctuous, though heartfelt, note to Frau Weingartner. Placing it in my little pink backpack, bundling up against the bitter chill, I grab the bag with its swilling mess and casually drop it into a trash can on my way to the U-Bahn. I finally arrive at the station closest to Frau Weingartner’s own flat. I had hitherto only associated Spandau with Rudolph Hess, the sole prisoner in its prison for decades. The district office tower looms over me as I consult a foldable Falk map. Ah, there’s Frau Weingartner’s flat, whose address I’d been given in case of emergency. Exploding toilets, considering the munitions of that particular detonation, surely count as emergencies. I make sure to buy the largest bouquet of flowers available.

When I ring below at the street, there is no answer. Fortunately, the ground floor door is ajar. Up and up I climb, clutching the bouquet close. Outside Frau Weingartner’s door, I ring and even knock. Waiting, I hear nothing. Then, I place the floral garland on the doormat with my note snuggled atop. Pausing, I look down at my sacrifice to Hestia, the goddess of the hearth.

The next day, Ulrich calls. Frau Weingartner was bursting with delight at the groveling letter and extravagant oblation. After this point, she no longer visits my flat, except to pick up the rent.

* * * * * *

Only decades later do I realize that Frau Weingartner had probably been in her late teens or early twenties when the Soviets barged into Berlin at the end of the war. We all know what had happened to females—elderly, mothers, and children—at that time.

I don’t know the story of Frau Weingartner. But I do know this: she would be welcome into any flat of mine at any time—even if she did chastise me for flushing improperly.

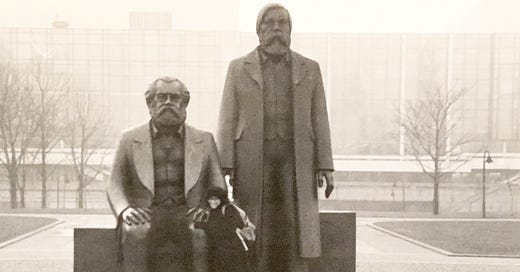

A Texas-based professor of medieval literature, Dr. Susan Signe Morrison has long been committed to bringing the lives of women hidden in the shadows of history to a wider audience. “The Landlady” constitutes one chapter from a book she’s writing about her Stasi or secret police file, kept on her when she lived in West Berlin 1988‑90 and taught in the former East Germany. This file contains multiple unusual (and false) assertions. Unbeknownst to her at the time, the head professor in East Germany was her Inoffizielle Mitarbeiter, or unofficial collaborator, reporting on her to the Stasi. Nevertheless, through his intervention and invitations, she was invited to return periodically to East Germany to teach. Using multiple documents, including her journals, personal letters, and official documents like the Stasi file, she’s creating a narrative investigating the past. She’s on an artist residency through the Cordts Art Foundation in Berlin for the summer of 2024, working on this book.

*All photos were provided by Susan Signe Morrison.